"Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government, nor of dungeons to ourselves. Let us have faith that right makes might; and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty, as we understand it."Abraham Lincoln, Speech on Slavery, Hartford, Connecticut, March 6, 1860

"President Lincoln Entering Richmond"

One of the books I purchased then, which I still have, is a first edition of the Lincoln Douglas Debates printed in 1860. While reading the transcripts of the debates I noticed that Lincoln tempered his anti-slavery comments in speeches he gave in Southern Illinois. Later, I learned that Lincoln had fired General George C. Fremont for refusing to rescind an emancipation order he issued in 1861 freeing slaves held in Missouri. Lincoln's actions - motivated by his unwillingness to jeopardize Missouri's membership in the Union - made it clear that his emancipation policy was motivated more by military exigencies than by a desire to end slavery. Lincoln also sanctioned the arrest, imprisonment and deportation of newspaper editors and local politicians who publicly expressed opposition to the war, and suspended the writ of habeas corpus, one of the most important of our Constitutional freedoms. Other Presidents, most notably Woodrow Wilson, have taken similar actions in time of war, and Franklin Roosevelt sanctioned the forced relocation to concentration camps of Japanese citizens solely on the basis of their ethnicity. I came to believe that their was nothing extraordinary about the moral character of President Lincoln. He was like no different than any other president who was willing to compromise his principles if he believed it necessary, or even expedient for him to do so.

The more I learned about him, the more I realized that Lincoln was not like any other politician. I now believe that all other Presidents should be measured and judged by his conduct while in office. Two little known events that occurred during the Civil War in the Fall and Winter of 1862-1863 define Lincoln's character and, in my view, raise him head and shoulders above other presidents who are considered great men, but who failed similar tests during their presidencies.

The Fall and Winter of 1862-1863 was a difficult time for President Lincoln and the Army of the Potomac. In August, the Union forces had suffered a devastating defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run. The Confederate army almost succeeded in cutting off the Union Army from Washington, D.C., an event that would have forced the evacuation of the city. In September, Confederate General "Stonewall" Jackson captured Harper's Ferry, in West Virginia, along with a garrison of Union soldiers and a stockpile of supplies. Three days later McClellan fought Lee to a draw at the Battle of Antietam in Maryland. In early November, Lincoln removed McLellan as the commander of Union forces. He was replaced by General Burnside who marched the Union army into another defeat at the battle of Fredericksburgh during the second week in December. The ability of the Union army to defeat the Confederates was in doubt, and the naval intervention of foreign powers to break the blockade of Southern ports was still a threat.

On December 17, 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant issued General Orders No. 11, a directive expelling all Jews from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi. General Orders No. 11 was motivated by Grant's frustration with Jewish peddlers whom he claimed ignored restrictions on travel and traded in black market cotton. The language of General Orders No. 11 was broad, and the army immediately started forcing Jews from their homes, in some cases giving families no more than 24 hours to evacuate.

At a time when the only thing standing between the Confederate army and Washington, D.C., was the good faith and skill of his generals, Lincoln didn't hesitate to countermand Grant's order. On January 3rd, 1863, two days after the emancipation proclamation went into effect, Lincoln directed that General Orders No. 11 be immediately revoked. President Lincoln explained that "he would allow no American to be wronged because of his religious affiliation."

During the months of August and September in 1862 an uprising of Dakota Sioux in Southwestern Minnesota lead to the deaths of approximately 500 settlers and soldiers. The uprising was put down by U.S. troops led by General Alexander Pope, who was sent west after his stinging defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run. At the end of hostilities, the U.S. military held 2,000 Dakota men, women, and children as prisoners. A military commission was established to try those Dakotas charged with murdering or raping settlers.

The ongoing Dakota trials were brought to the attention of President Lincoln during a cabinet meeting on October 14th. On October 17th General Pope informed the Commission that "the President directs that no executions be made without his sanction." In a matter of weeks, 398 Dakota men were tried by the Commission, all without the benefit of counsel. The Commission convicted 328 of the Dakota defendants and ordered that 308 be hanged. Upon hearing of the verdicts, President Lincoln asked for "a full and complete record of [the] convictions" and "a careful statement" indicating "the more guilty and influential of the culprits." On November 15, the records of the trials were forwarded to President Lincoln. Accompanying the records was a letter from General Pope urging the President to authorize the execution of all of the condemned. Pope's letter warned of the danger of mob violence if the executions were not carried out immediately .

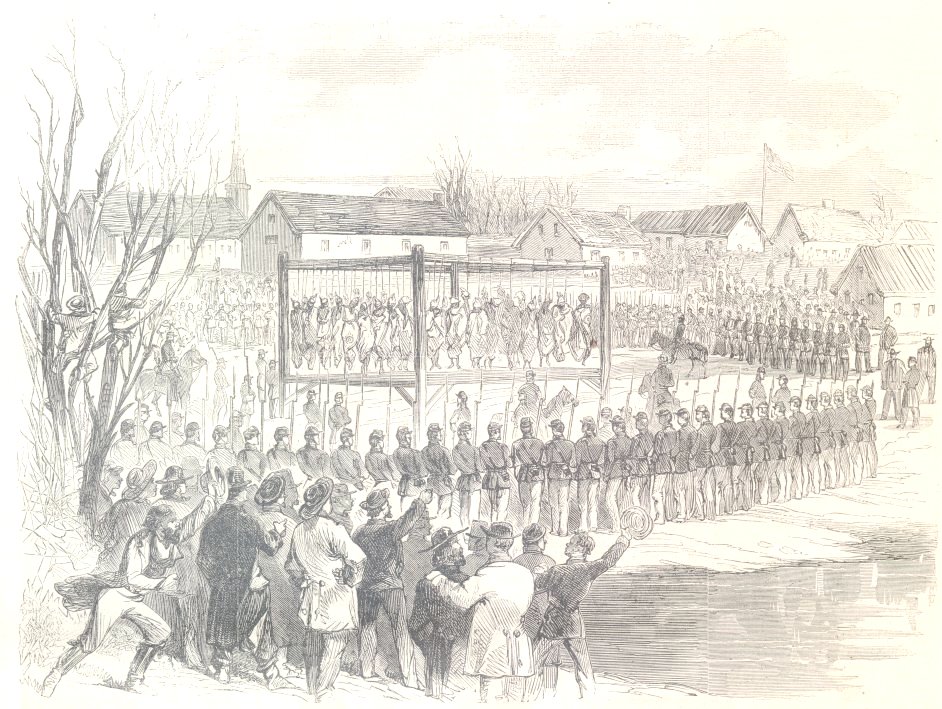

With the outcome of the Civil War uncertain, and battles raging within a days horseback ride from Washington, D.C., President Lincoln took the time to review summaries of the trial records prepared by government lawyers and considered the fate of all 300 Dakota defendants still awaiting execution on the Northwestern frontier. On December 4th, two days before President Lincoln's made his decision, soldiers surrounded and disarmed a lynch mob of several hundred settlers who had attacked the camp were the Dakota prisoners were being detained. On December 6th President Lincoln issued an order allowing only 39 of the planned 300 executions to go forward.

It would have been easy for Lincoln to not involve himself in these peripheral matters and delegate their resolution to a subordinate. Instead, he believed that the ethnic cleansing of thousands of citizens, and the imminent execution of 300 potentially innocent Native Americans, were of such grave concern that they deserved the direct and full attention of the President of the United States; even during one of the most crucial and potentially dangerous periods of the Civil War. For Abraham Lincoln - at least in these two instances - Due Process and the Rule of Law trumped even the exigencies of war.

No comments:

Post a Comment